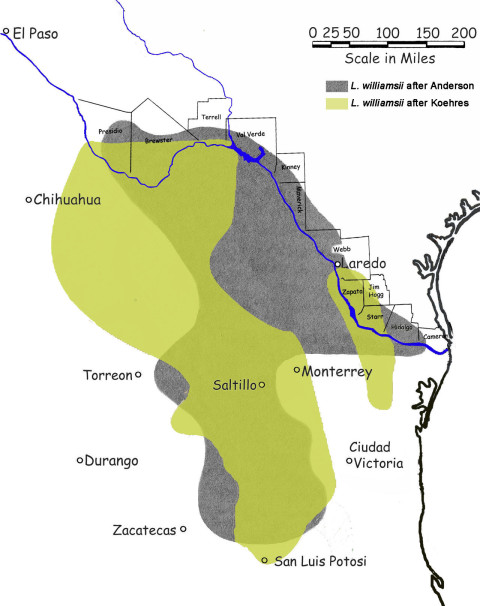

Description and characteristics of Lophophora williamsii

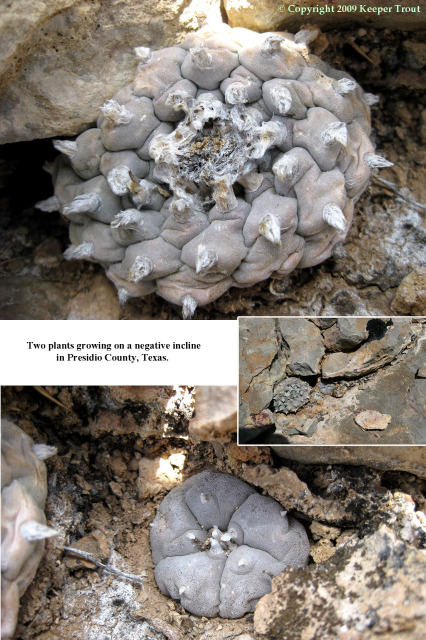

Plants are typically low growing, often almost flush with the ground. (Sometimes occurring as low mounds.) Rains and resulting water flow can rearrange the top surface of the soil leaving peyote plants with up to several cm of exposed stem or they can become completely buried by several cm. They are specialized at growing on sloping terrain.

During times of drought, and in preparation for winter, peyote can pull itself into the ground. New growth will occur as soon as favorable conditions return.

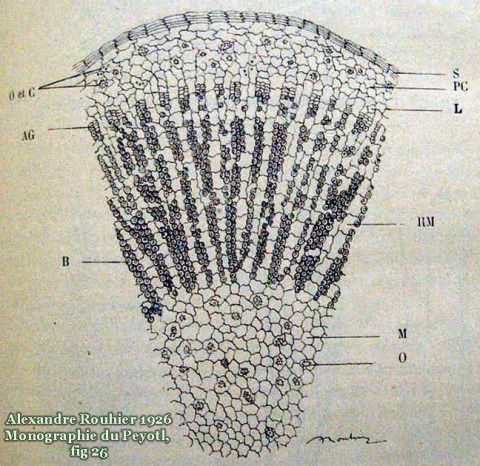

Peyote has a deep taproot that is napiform (fat carrot or ice-cream cone shaped in general outline), tapering slowly from the above ground portion’s diameter, and weakly branching mainly at the distal end. It can be seen in instances such as Henning’s Anhalonium williamsii illustration that roots can sprout from almost anywhere on a cut peyote plant after it has been replanted.

Especially towards the top there are greyish or brown coarse barky rings, formed by the shriveling of the outermost row of areoles that are becoming the top part of the nonchlorophyllaceous stem.

The roots are usually 8-11 cm long (4.) 3-5 inches long (5.)

Crown broken by passing traffic showing a cross section of the stem, the vascular bundle and the barky outer layer

Only with substantial age will the roots on rooted cuttings get tap-root like. Cuttings can never reform the single fat root peyote is noted for but each of their pups can go on to form their own tap roots, especially after their mother was decapitated. In this latter case the rootstock of the mother may eventually be sucked dry of life as the pups go on to become independent plants.

The roots that form are often whitish to tan, fleshy and weakly branching.

pups forming separate roots following crown death (due to rot) of the mother Cactus Conservation Institute image

Roots that form tend to branch primarily at their base and only sporadically and weakly as this partially uncovered young plant illustrates. Notice how similar the branching of this seedling is to the branching of the solitary herbarium specimen that was shown earlier.

Grows as, often dwarf, solitary heads. Occasionally budding at the base to form pairs or clusters. Budding occurs rarely in young plants and is more frequent in older plants. Many plants remain single, even if large. Small intact plants of double heads are sometimes encountered. One that initially looked cristate within several years had divided into two perfect heads.

Many times plants can be found joined underground. This is especially noticeable on plants which have pupped due to flush cut harvesting. As the wound heals, the cactus shrinks into its root and the pups form from an old areole on the subterranean stem, this most often occurs underground.

It must be mentioned that some people cut the plants below ground level and apparently obtain clumps as a result. It is clear the mortality goes up but how much has seen very few studies. The lower the cut the less stored tissues remain. If the cut is above the subterreanean stem there is almost a certainty of regrowth. If it occurs below that transition and leaves just root tissue there is no chance of regrowth as the requisite areoles were removed. If the cut falls someplace within the nonchlorophyllaceous stem itself there is still a chance for regrowth but the mortality goes up as the stored food reserves goes down adding an increased susceptibility to extremes of drought and weather. (See the studies of Terry & Mauseth 2006 for details on morphology and Terry et al. 2011, 2012 & 2014 for details on post harvesting regrowth and mortality.) One factor interfering with an adequate perception of loss by harvesters is that when deep cutting kills a plant the carcass often decomposes under the earth leaving no trace.

The base of pups not induced from injury only occasionally send out, mainly weak, roots of their own. Often in previously harvested rooted heads, there is no independent formation of roots by the resulting pups and they rely on the vascular system of the mother. Unless forcibly divided [Note 18] the pups remain connected as a part of the parent. In cases where the mother plant has been compromised or dies the pups can and do go on to form new tap roots.

In clumps, there is often one plant far larger than the rest unless clumping was induced by injury. New plants forming from injury, especially partial decapitation, are usually produced from the healthy and intact areoles peripheral to the injury, and, if multiple, will normally be of the same size. All variations of growth can normally be found in a large population of old plants.

Pupping is enhanced greatly by injury, especially if to the terminal portion of the head (apical meristem).

Occasionally peyote forms large mounds with great age. Mounds over a meter in diameter have been reported by many different reliable sources. Weniger says “often clustering to form up to 50 [heads] in one variety.”

These mounds are rarely encountered in Texas anymore. It was not always this way.

The heads are rounded and usually more or less flattened on top. The center of the top is depressed and filled with woolly hair. They may be globose or somewhat cylindrical but all have depressed centers except when severely etiolated [Note 19] (6.).

Peyote infrequently forms crests [Note 20] but these are not infrequent in major cactus and succulent collections as they are highly sought after by cactus collectors. It is probable that crests can occur in any of the wild populations and in any Lophophora species. Occasionally, they are offered for sale as horticultural specimens that can sometimes exceed a foot in diameter. Belgian seed suppliers have offered seeds from cristate plants but it is doubtful crests would develop on the offspring. They showed no germination, in contrast to the ready germination of their other “species” and varieties.

More images can be found at sacredcacti.com

Pictures of a crested specimen can be found on Page 2904, fig. 2732 of Backeberg 1961 and on page 178 (# 738) in Hirao 1979 and also on page 1298 of Lamb & Lamb 1978 and on the back cover and pages 44 & 45 (as in-habitat color photos) in Grym 1997 and also in the black & white plate facing page 177 of Martin et al 1971.

A very useful search phrase for amazing images is “烏羽玉綴化“.

Lamb & Lamb commented that peyote crests grow quite well on their own roots so that grafting is not necessary (unlike many crests which are slow growing and rot prone.) Grafting of peyote crests is a common practice though as it is how most crests are multiplied for commercial propagation.

Lophophora williamsii echinata from Val Verde County starting to develop a crest. Cactus Conservation Image

Plants are firm and very succulent. Said by Lamb & Lamb 1974 and Weniger 1984 to be soft but I have found them only to be soft when in poor health or wet such as after heavy or prolonged rains, especially if during cool weather. Normally they are turgid and firm as a green tomatillo, but with an almost velvety feel. The friendly ‘touchability’ of this plant may be a part of its allure for many otherwise mainstream cactus growers.

The flesh of peyote, like many other cacti, typically has a gritty or sandy texture due to the presence of oxalate crystals as can be observed exposed by a predator in the image below. (In some cacti such as Echinocactus horizonthalonius oxalate can comprise 60% of the dry weight of the entire plant!)

Peyote may be blue-green, greyish-green, bright glaucous green (usually only seen in bloated overfed cultivated plants), chalky blue and occasionally appearing reddish-green. All usually have a pronounced grey glaucescence or haze on their surface unless it has been abraded off by rough handling. This haze on their surface is due to a layer of small flakes of waxy material. Brown areas can develop during droughts and reddening or even purple coloration can be induced by cold and freeze stress.

Anderson notes that a brown corky layer of unknown origin sometimes develops on cultivated specimens. This was encountered this once in a wild population in southwestern Zapata County. It doesn’t seem to hurt the plants but when present, sometimes spreads and becomes unsightly. I’m at least assuming this is what Anderson refers to:

There are no leaves except microscopically during early development. (2.)

Literature gives sizes usually falling in the 4-12 cm. in diameter and 2-8 cm. tall range.

Weniger says Lophophora williamsii var. williamsii reaches 3 inches and var. echinata reaches 5 inches (5.)

In previous editions of Sacred Cacti I mentioned seeing larger – huge – many-ribbed Lophophora williamsii in the late 1970s. I now believe this was in error and that ALL of those plants were actually Lophophora fricii. I now believe that I was being lied to by the collector concerning their point of wild-collected origin.

Plants over 4 inches have always been of rare observance. Weniger comments that “var. echinata” can reach five inches in the longest dimension of its crown. Bohata et al. 2005 also pointed out the existence of some interesting larger Lophophoras in Mexico. They appear to need some study.

Normally Peyote reaches somewhere towards 3 or 4 inches and then fluctuates in size seasonally, occasionally by as much as an inch in all directions, for the rest of its life. It will continue to grow larger only in the sense that the root will continue growing into the earth, the crown will continue to replace most of what tissue is lost due to local environmental extremes and predatory challenges, and, in many cases, pups will be produced by the original stem.

Notice the extremely long roots in this next image (modified from Bravo 1937). It must have taken a long time the plant on the right to go from being a seedling to having its roots that deep in the earth. Hopefully the viewer noticed how the diameter of the plant itself did NOT steadily continue to grow larger during that process.

In the neighborhood of 8 ribs is what is most often thought of with peyote but the number is highly variable in any population. Anderson 1980 says 4-14 ribs. If a peyote has more ribs than 14 it should be suspected to be Lophophora fricii.

5 ribbed plants are rare past somewhere around one inch in size. Only occasionally do they not soon go on to form more ribs. While some authors have stated that it is simply a juvenile form of the plant, 5 ribbed plants do occasionally reach at least 3 inches in diameter and other 5-ribbed plants will sometimes stay tiny even with age.

More images can be found at sacredcacti.com

The ribs are defined by furrows which are easily divided in a cut plant, and may be straight or in spirals. Sometimes the ribs are irregular or even indistinct. Usually they are broad and rounded and have shallow transverse furrows, forming tubercles or podaria. Schultes & Hofmann 1980 refer to them as “more or less regular, polyhedral…” and Benson 1982 calls them “irregularly hexagonal”. They may bulge outward but especially in older tubercles they tend to flatten out and become low, broad and rounded. They can reach an inch in “diameter”.

The ribs and tubercles or podaria are highly variable in appearance from individual to individual, as well as seasonally. Part of the reason for this is that the ribs serve an important function for cacti as they enable the body to swell or contract in response to the available water.

The highly variable nature of peyote’s appearance underlies the problems it gave some botanists in Europe who had never seen an actual population first-hand (it has also caused many problems even for those who had field experience).

Many more images can be found at sacredcacti.com

Areoles are usually arranged linearly along ribs or at the apices of the hump-like tubercles or podaria. They are set from 1/2 inch to 1 inch (1.3-2.5 cm) Lamb & Lamb, 0.9-1.5 cm Anderson, 12-25 mm Benson, apart. The areoles are flat and round. They range from 2 to 4 mm in diameter.

The areoles in peyote only bear flowers when young.

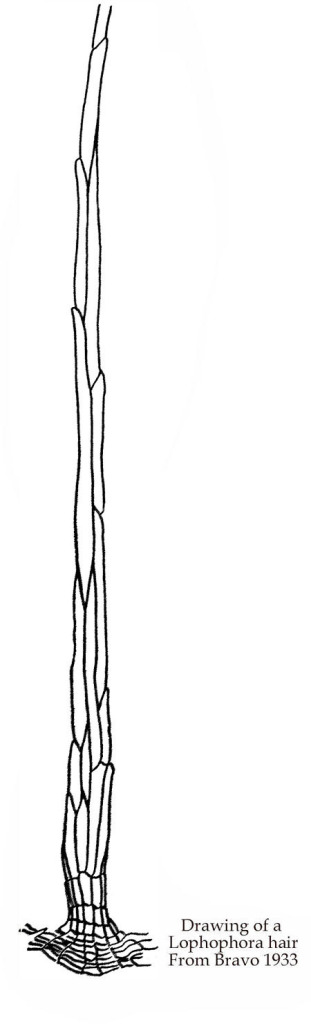

During the first year of growth each areole bears a dense tuft of white and more or less silky hairs to 7-10 mm long. (2.)

Later, each mature areole bears a dense, cylindroid tuft of soft trichomes (woolly hairs), 8-15 mm apart, 1-5 mm in diameter. (1.)

The persistent tufts of hairs are usually equally spaced on the ribs. (4.). They usually feel silky and may stand erect and matted or have the ends bent or broken off entirely.

Wool is yellowish or whitish, usually turning grey with age and it is sometimes broken or worn off.

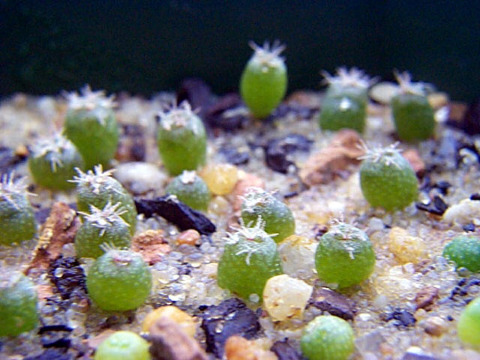

Spines are usually absent except in very young seedlings which bear a few weak bristle-like, usually white, sometimes yellowish, spines on their crown.

While this is what is easily observed, Mauseth 1983b points out that peyote does in fact “…have spines, but they are so short that they do not even reach the top of the depression in which the areole is located.” However, occasionally tiny spines can show up noticeably on wild L. williamsii.

More images can be found at sacredcacti.com

A known exception to this concerns those plants referred to as L. jourdaniana which normally show some longer & quite noticeable spines, especially on young areoles.

Both flowers and fruits form on young areoles, near apex of stem, [borne at umbilicate centre of crown, (4.)], each at apex of a low new tubercle in a felted area adjoining the spine-bearing part of areole and partially merging with it. A circular scar persists at the site after the fruit has fallen. (2.)

Flowers are normally solitary but occasionally there will be several flowers either rapidly following each other or blooming together. 5 is the most I have ever witnessed first-hand. They couldn’t open fully because they were so close together. See photo of 3 in McLaughlin 1973 and in Schneck. See Mount 1993 for a picture with 5 blossoms open at one time.

Flowers are 1 cm to 2.5 cm in diameter, and 1-2.4 cm long (3 cm long. 2.). The floral tube has been described as “rotate-campanulate”(4.), “funnelform”(2.), and “bell shaped”(5.). Each flower is surrounded by a mass of long hairs.

Flower size, color and petal shape can be variable even within single populations. Pinkish, whitish blushed pale pink or rose (5.) are the most common flower colors. Dirty white, pure white, or pale yellow yellow are very rarely encountered.

More images can be found at sacredcacti.com

Populations observed in Texas usually were light pinkish with a darker pink, occasionally greenish, mid-stripe on each petal or whitish with a pink mid-stripe. More rarely they were whitish sometimes having a faint greenish mid-stripe on each petal that is most colored on the outside.

More images can be found at sacredcacti.com

The flowers in Weniger’s echinata have so far have had light pink petals with a darker pink midstripe. (6.) They have tended to be a bit more oval rather than round.

More images can be found at sacredcacti.com

Outer perianth segments and scales ventrally greenish, callous tipped (4.) Outermost perianth segments greenish with entire edges (5.)

Sepaloids with greenish middles & pink margins, largest narrowly oblanceolate, 9-15 mm long, to 3 mm broad, acute and strongly cuspidate, the margin entire. (2.)

Outer perianth segments have greenish midribs and greenish-pink or whitish margins, the largest ones elliptical, 3-12 mm. long, 1-3 mm broad, mucronate, marginally minutely ciliate distally (1.)

[Outer perianth segments = sepaloids = sepals]

Inner perianth segments pink, pinkish-red, or white, often with a darker midstripe, the largest ones are typically elliptical, 8-22 mm long, 2-4 mm broad, mucronate or occasionally attenuate, margins ciliate or entire. (1.)

Inner segment almost linear, pale pink to rose, white or yellowish. (5.)

Petaloids often pink in their middles, pale to nearly white at margins, largest oblanceolate, 12-15 mm long, to 4 mm broad, acute and cuspidate, entire; filaments pale, more or less 2 mm long. (2.)

[Inner perianth segments = petaloids = petals]

Flowering will usually begin around 5-6 years of age (or when they reach around 1 inch in diameter) from seed. It can begin much sooner if they are grafted; often within a year after making the graft even if starting with a young seedling.

The style is white, tinged with pink, reddish or rarely magenta, to 9 mm (2.) [5-14 mm (1.)] long, more or less 1-1.5 mm at greatest diameter;

The (3-)5-7 lobed stigmas are naked, linear, thin and flattened; 2 mm long, 1+ mm broad, and can be reddish, pink or yellowish;

Ovary is small, naked and surrounded by hairs (to 12 mm long). “Ovary in anthesis [is] turbinate”, 3-4.5 mm. long, smooth, not scaly. (2.)

Filaments are whitish, or rarely magenta (1.) and shorter than perianth segments (4.).

They bear 3-7 yellow anthers, 1-1.4 mm long.

The stamens of L. williamsii are thigmatropic so respond to touch by curling. A toothpick was used to gently touch the anthers in the photo below.

More images can be found at sacredcacti.com

The pollen in L. williamsii is highly variable in size, shape and aperture. The grains are more or less spheroidal (around 12 different geometric shapes), 0-18 colpate, and is (14.9-) 26-63.4 mm in diameter (averaging 40 microns) (1.) [Image]

[See also Anderson & Stone 1969]

Normally flowering from March through September (1.)

There are usually two peaks of flowering, one in spring and one in summer, generally these are following rain.

Cultivated plants have been observed to flower both earlier and later and can seemingly occur any month of the year if the conditions are right (6.)

Pizzetti 1985: entry #154. Has picture of a plant with a flower and pups.

Innes & Glass 1991 Also features a nice color picture in flower; on p. 150.

Color pictures can also be found in Grym 1997.

Fruits are small, slim, elongate, nude and clavate (club-shaped), or nearly cylindroid and enlarged gradually upward, (12-)15-20 mm (1, 2.) (3/8-3/4 inch) (5.) long, more or less (2-)3-5 mm diameter (1, 2.) The umbilicus is large or the perianth parts persistent, and the fruit emerges rapidly from within the trichome at maturity.(1.)

They are red to pale pinkish when ripe. Fleshy and indehiscent at first, they become dry and brownish-white, or eventually blackish, at full maturity. Seeds are released by the pods drying and breaking.

The fruit walls are thin, transparent when fresh, and bare, without tubercles, scales, spines, hairs or glochids, although a few small hairs can rarely persist on the end of the fruit.

Fruits mature 9-12 months after fertilization. (1.) It is common to find fruit emerging around the same time as the flowering periods. Gerhard Koehres (who has extensive experience with commercial seed production using grafted seedlings) has commented that fruit can form from the early flowers within around 8 weeks but has also found that the fruit for the later blossoms often do not emerge until the following year. Clearly this subject is apparently not as cut and dried as was presented by Anderson and merits some study.

Seeds are usually are spread by water and possibly sometimes with the help of ants. It is almost certain that ants harvested the seeds from this Lophophora fruit in Presidio County.

Whether they are what is responsible for the placement of these two plants with their crowns at an almost vertical orientation is a matter of fascinating speculation.

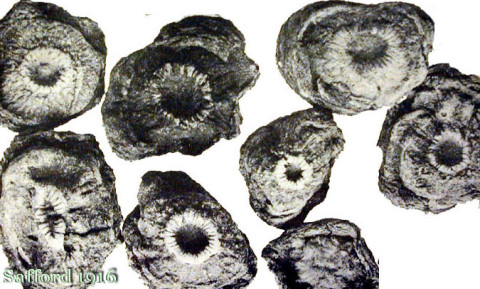

Seeds are black, tuberculate-roughened (4.), (verrucose) pyriform (1.), densely papillate (2.), longer than broad, 1-1.5 mm. (2.) [“about 1/16 in.” (5.)] long, 1(+) mm broad, 0.8 mm thick; with broad whitish basal hilum (large, flattened, depressed and sometimes v-shaped), enlarged upward from the hilum, resembling those of Cereus (2.), Ariocarpus and Obregonia (1). [Image]

Check out all those seeds. You can actually see the shape of the hilums clearly in the larger viewing sizes!

They set seed readily even in cultivated plants. It is not uncommon to find seedlings growing in with older specimens.

Cotyledons coalescent (1.), accumbant, not foliaceous. (2.)

Chromosome number 2n=22

The closest living relative to Lophophora williamsii, based on the molecular cladistics of Rob Wallace, is Obregonia denegrii.

Description adapted from (1-5 include pictures.)

1. Anderson 1980: pp. 179-181.

2. Benson 1982: pp. 680-683.

3. Lamb & Lamb 1974: pg. 196.

4. Schultes & Hofmann 1980: pp. 221-222.

5. Weniger 1984: pp. 138 -140.

6. Personal observation.

Useful search terms for locating additional imagery:

烏羽玉 & 乌羽玉(Lophophora williamsii)

子吹乌羽玉(Lophophora williamsii f. caespitosa)

乌羽玉缀化(Lophophora williamsii f. cristata)

大型乌羽玉(Lophophora williamsii “var. texensis“)