A Trichocereus sold as San Pedro (Peru)

Claimed to have been collected from the slopes above Matucana but corroboration would be nice.

This is one of a few from this vendor (HdP). Several of the others can be seen at http://troutsnotes.com/sold-as-san-pedro-2/

Shows features that seem intermediate for pachanoi and peruvianus.

It will be interesting to see what this does with some good sun and free root run. I’m betting that the flowers are going to be awesome.

Over the years, Karel Knize has marketed at least half a dozen assorted short-spined collections of wild collected Peruvian plants falling into or in-between T. pachanoi and T. peruvianus under the name & collection number “Trichocereus peruvianus KK242“; all of which he asserted had come from a given range of elevations on the slopes above Matucana despite including geographic names like “Río Chillón” and “Río Lurím” which place them in completely different river systems (The town of Matucana is located in the canyon of the Río Rimac).

While all of the KK242 that Knize has sold as live plants have been either T. peruvianus or T. pachanoi and while some of Knize’s KK242 seeds have in fact produced T. peruvianus plants (for instance what was grown out by Abbey Garden for analysis by Pardanani), it is also true that far more of his seeds, apparently the majority of them, have turned out to be of T. cuzcoensis and some KK242 peruvianus seeds have grown into beautiful T. bridgesii plants. Then there is Knize’s Trichocereus peruvianus KK242 f. Matucana which is unmistakeably a pachanoi. Like so much from Knize, lots of beautiful plants accompanied by a perplexingly excessive amount of noise and confusion about their origins and identities.

Karel Knize actually gives Curt Backeberg a run for the money so far as which weighing which one of the two contributed the most confusion into the world of cacti and cactus nomenclature.

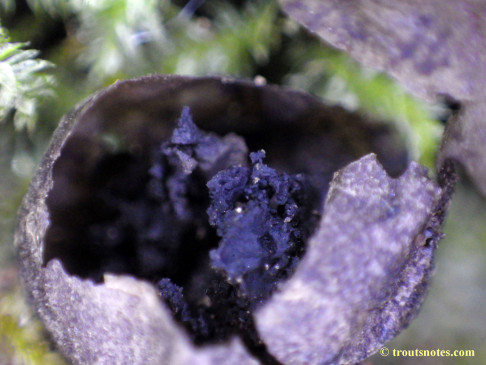

However, Grizzly shared these images a few years back from that same locale above Matucana, Peru:

This has been disputed and a counterclaim has arisen that short spined T. peruvianus forms do not exist anywhere around Matucana. (The same person insists that no pachanoi occur in the area except for one single person’s plant which is cultivated inside of town.) Since collections from three sources are also known that claim does not seem to have always been the case but perhaps it is a conclusion that may be true now? Or perhaps the friend dismissing it simply visited too soon after Grizzly’s harvest and no new growth had become visible? I do not know as I have never been to Matucana to find out. Grizzly commented on them being uncommon. Considering that what they found was cut down and chopped into pieces and the other two claims for short spined peruvianoids from above Matucana were both commercial cactus vendors who were selling them as cuttings, perhaps that may hint at one possible reason underlying the perception of scarcity, lack of visibility or even absence?

I am reminded of a joke about an entomologist bragging that he had finally managed to pin enough individuals to elevate the ranking of an endangered species from G2 to G1.