South American Trichocereus pachanoi

compared to

the predominate “pachanot” cultivated in the USA

This page is a bit image heavy. . .

As was mentioned previously, I began referring to this as pachanoi PC out of laziness, namely when growing tired of typing or speaking using ‘the predominate cultivar of Trichocereus pachanoi‘ as a noun. Or PC could as easily refer to the ‘predominate clone’ since it does seem to be produced entirely vegetatively despite it freely flowering & readily hybridizing — or *maybe* it should stand for politically correct, I don’t know. (I do know that I have grown to doubt that it is actually a pachanoi and am presently suspecting it may be a pachanoi hybrid. Let’s come back to that later.)

Questions have been raised about the culturecentrism of this “PC” view as a basis for a designation. As it is not necessarily the predominate cultivar elsewhere in the world this term PC needed abandonment and replacement. Not for sake of proposing a name but simply to be able to have a unique noun to be able use as a term of reference so we can discuss the matter.

As a result, in this discussion it is jokingly referred to as Trichocereus pachanot.

This is the primary Western cultivar sold in the US under the names Trichocereus pachanoi, San Pedro and sometimes as Echinopsis peruviana in southern California.

This is that same bona fide pachanoi growing in a shaman’s garden near Cuzco

(Photo copyright by Geneva Photography)

Notice the details of the flowers and how smooth edged this plant is? Also how indented/sunken the areoles are and the planar relationship they have to the median of the rib? Take a closer look here or farther below. Now go back to Backeberg’s pachanoi photo and compare this and then compare both to the pachanot.

Spines here and in Backeberg’s photo are shorter than on the pachanot but spine length is something that can almost be disregarded (within reason) for being a variable characteristic. When they have short spines, it is a common thing for the short expressions of the spination on pachanoi to be consistently much shorter than the already short spines of the pachanot.

Many of the trichs show ranges of characteristics rather than set characteristics so it is easy to become diverted from some important points concerning the predominate cultivar.

a) It does not match the description of pachanoi as given by Rose & others in perhaps minor but very consistent ways.

b) It is readily differentiable from the pachanoi that seems to be most common in Ecuador and Peru. This is true of its morphology, its floral elements and its fruit.

c) Thus far it has NOT been encountered in the wild or in use among Peruvian shamans.

d) It shows characteristics of both its flower and its fruit, as well as intensely vigorous growth, that are suggestive of it being a selection derived from a hybrid.

e) It is dramatically lower in alkaloid content than a bona fide pachanoi such as would be selected for ceremonial use by a shaman in Peru.

While a pachanoiXbridgesii is at least plausible, there are other possibilites.

We may never know the answer with any degree of certainty – perhaps not even with a lot of work that is yet to be done.

Below we will soon be seeing a series of typical pachanoi from South America compared to the pachanot that we most commonly have growing in the US.

The first images were shared by MS Smith who brought this subject to my attention in the first place. All of these images are said to be of Ecuadorian pachanoi.

The one on the left is said to be a photo of a voucher collected in Ecuador by Timothy Plowman. The ones on the right were said to be taken in Ecuador as well.

I do not know their photographers.

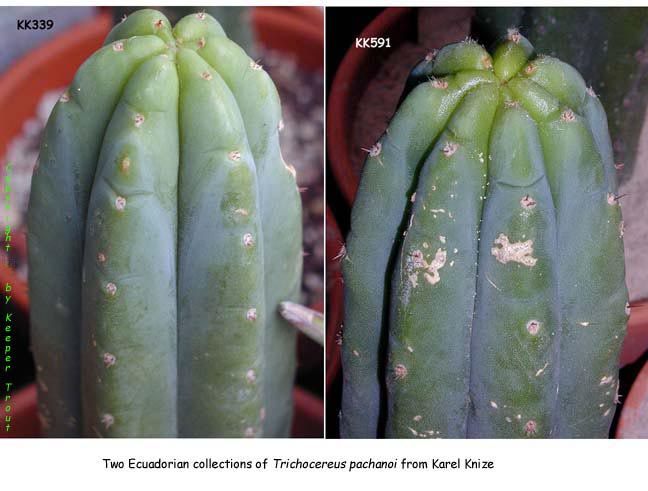

These next two tips are both Ecuadorian pachanoi sold by Karel Knize in Lima, Peru and shipped to Texas.

Now this is going to start to get interesting. Or perhaps at some point it will become just boringly repetitive, so feel free to skip ahead whenever that happens to you.

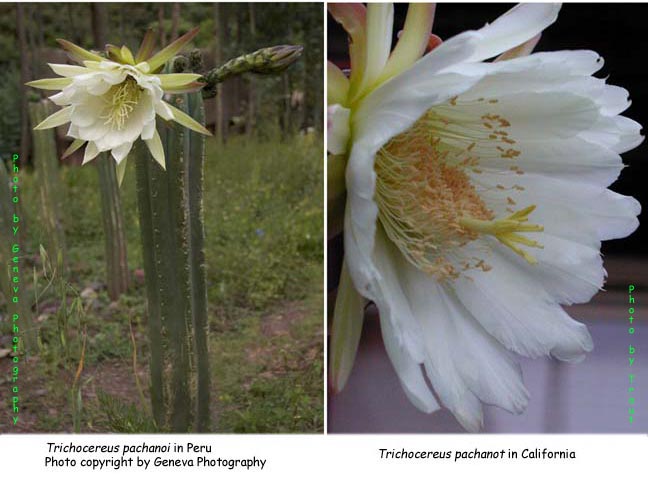

On the left below is a pachanoi in Peru and on the right is a US horticultural pachanot.

Pay particular attention to the spination, areoles, flower buds, flowers, pericarpels, tubes, scales, hairs arising from the axils of those scales, the fruit and the contour of the ribs.

Ecuadorian pachanoi from Knize (KK339) on the left and on the right pachanot

Ecuadorian pachanoi from Knize (KK339) on the left and on the right pachanot

bona fide pachanoi can sometimes be encountered in the US as is shown on the left (Photo by Anonymous) and on the right is our pachanot again.

Peruvian pachanoi on the left (photograph by Grizzly) and on the right pachanot.

Peruvian pachanoi from Matucana (photo from Kitzu) on the left and on the right pachanot.

Ecuadorian pachanoi from Knize on the left and on the right pachanot.

Ecuadorian pachanoi from Knize on the left and on the right pachanot.

Ecuadorian pachanoi from Knize on the left and on the right pachanot.

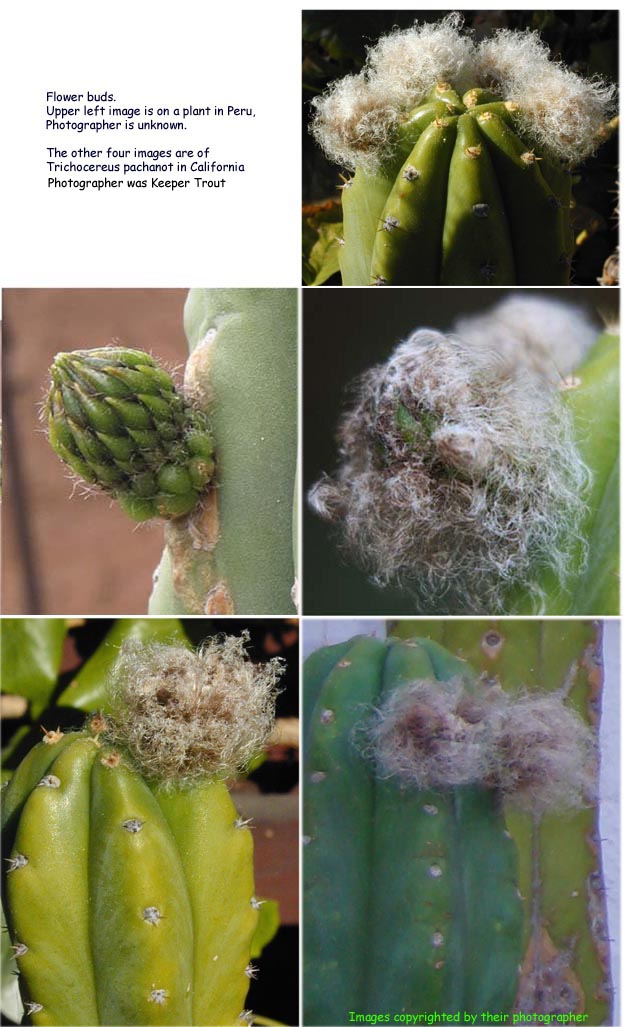

Flower buds

Upper left image is from Peru: Photographer is unknown to us.

The bottom left and the entire right column are pachanot.

Flower buds

In Peru on left (Geneva Photography)/ On right is the pachanot

A closer look

In Peru on left (Geneva Photography)/ On right is the pachanot

In Peru on left (Photographer?)/ On right is the pachanot

Ovary & tube

In Peru on left (Geneva Photography)/ On right is the pachanot

Flower tube/receptacle

Bona fide pachanoi growing in Oz is on left (photo by Zariat) and on right is typical US pachanot cultivar.

Flowers:

pachanoi near Cuzco, Peru on left (Geneva photography) and pachanot in Oakland, California on right

Flowers & fruit:

Peruvian pachanoi photographed by Friedrich Ritter is on the top left and two more Peruvian pachanoi are below it. The pachanot on the right were in California.

The next image is all the US pachanot cv.

For pachanoi the ovaries were described as being covered with black wool.

While these typically do show very short black or dark brown hairs along the axils of the scales on the tube and similarly on the ovary/fruit they are generally obscured by white and/or light brown and/or greyish wool and can be absent. Compare this with the examples of similar locations on the floral tube, ovary and fruit on the Peruvian pachanoi shown above.

Fruit:

Peruvian pachanoi on left. pachanot on right.

To bring this conversation back towards the elephant in the room:

If anyone wonders WHY this cultivar now predominates the US market almost to uniformity consider that it shows intense vigor permitting commercial operations such as can be seen below.

This shows but a small part of a single professional propagator’s mother plants:

(Photos by Anonymous)

Reflect on this undeniable observation: The pachanot is much faster growing, far more cold tolerant, and is both more rot resistant and more water tolerant than a bona fide Trichocereus pachanoi. In fact if a person pumps their pachanot with water it grows almost as well as watermelons.

The simple mechanics of its vegetative propagation combined with its popularity as an ornamental obviously would favor it becoming the predominate horticultural offering over a fairly short period of time (in this case a few decades – possibly as little as around fifty years if it involved Paul Hutchison but there is also evidence suggesting it might have occurred as long ago as the 1930s if it was something from Harry Blossfeld. A more detailed discussion of the existing evidence will be appearing in the next edition of the San Pedro book which will be available on this website along with the rest of Sacred Cacti 4th edition.)

A small group of friends and I are still actively searching for confirmation that this is what actually occurred.

It is now so prevalent in US horticulture that it is presently fairly rare to encounter anything else being produced commercially.

If anyone has more information concerning this plant’s origin, especially if you have facts to the contrary and/or if you can tell us its precise point of entry into US horticulture or offer any additional details, please contact us at:

pachanot

@

keepertrout

DOT net

All photographs are copyright by their photographers.

Photos are by Keeper Trout except where indicated otherwise.

Use your back button to return.

To go back to the article:

“pachanoi or pachanot?“

-

Smith’s observations

with excerpts from some published descriptions. -

Topic 1: Backeberg’s clone

-

Topic 2: pachanoi compared to pachanot. (Your present location)

Additional material to ponder:

Copyright © by Keeper Trout